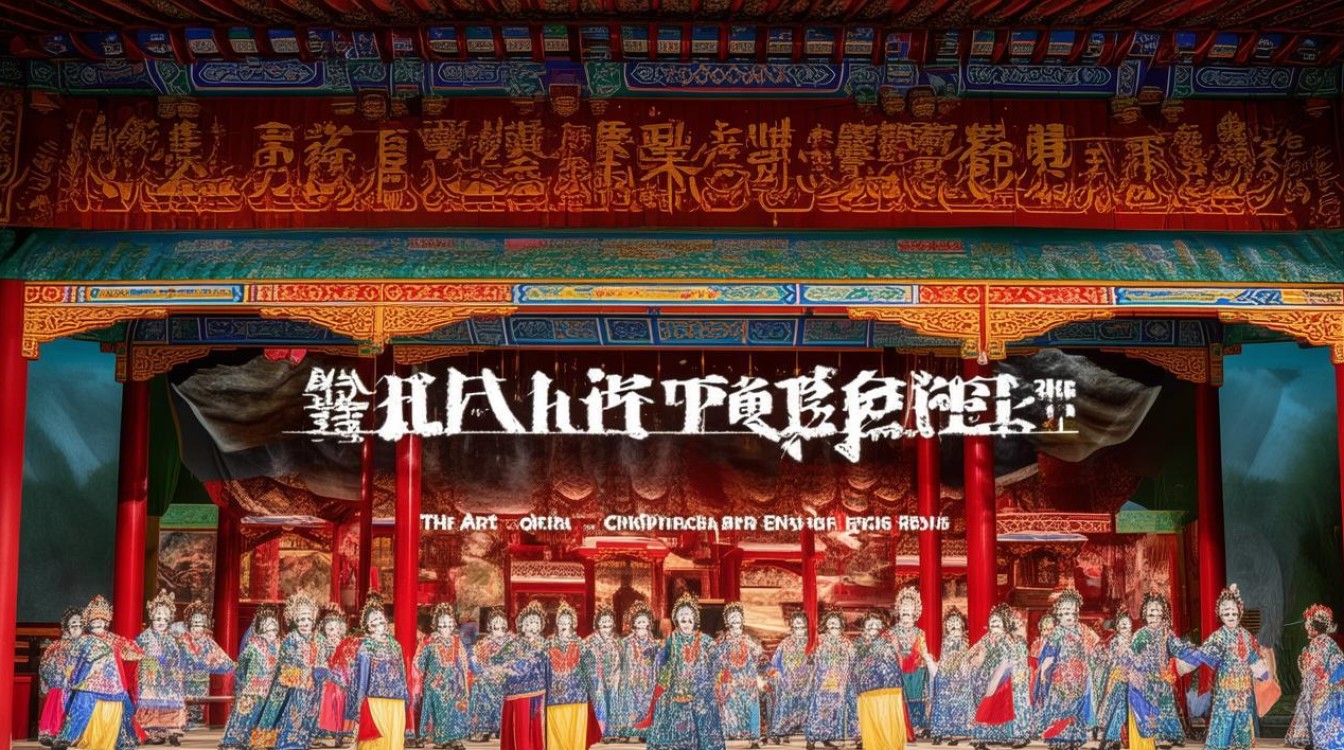

Peking Opera, with its vibrant costumes, intricate movements, and melodic tunes, stands as a jewel of Chinese traditional culture. For students and enthusiasts writing English essays about this art form, it’s not just an academic exercise but a chance to bridge cultures. Here’s how to craft a compelling piece that honors Peking Opera’s richness while appealing to global readers.

Understanding Peking Opera’s Core Elements

To write authentically about Peking Opera, grasp its four pillars: singing (唱), recitation (念), acting (做), and acrobatics (打). Each component demands years of mastery. For instance, the iconic dan (female) roles, like the graceful qingyi or vivacious huadan, use subtle gestures to convey emotion. Meanwhile, the jing (painted-face) roles rely on bold colors and exaggerated expressions to depict character traits—red for loyalty, white for cunning.

In an English essay, avoid dry descriptions. Instead, paint a scene: "The actor’s sleeves flutter like autumn leaves as he spins, his crimson face glowing under the stage lights—a general poised for battle." Such imagery engages readers unfamiliar with the art.

Historical Context: From Imperial Courts to Global Stages

Peking Opera emerged during the Qing Dynasty, blending regional styles like Kunqu and Hui opera. By the 20th century, legends like Mei Lanfang revolutionized it, introducing nuanced femininity in male-performed dan roles. His 1930 U.S. tour even influenced Western theater, proving art transcends language.

When discussing history, link it to universal themes. For example: "Mei Lanfang’s performances weren’t just entertainment; they were diplomacy. In a pre-internet era, his art became China’s silent ambassador." This frames Peking Opera as a dynamic, living tradition rather than a relic.

Why English Essays Matter for Cultural Exchange

Writing about Peking Opera in English serves two purposes: preserving heritage and fostering dialogue. Consider the essay’s audience. A student might compare Peking Opera’s symbolism to Shakespearean soliloquies—both use stylized gestures to express inner turmoil. A traveler’s blog could focus on the visceral thrill of live performances: "The drummer’s rhythm matches your heartbeat as the actor leaps across the stage, defying gravity."

Use accessible analogies. Describe the erhuang melody as "the blues of Chinese opera," or liken face-painting to Venetian masquerades. This demystifies the art without diluting its uniqueness.

Common Pitfalls to Avoid

- Overgeneralizing: Not all operas feature acrobatics. Regional variations exist.

- Ignoring Modern Adaptations: Contemporary troupes experiment with digital backdrops or feminist retellings.

- Dry Terminology: Instead of "Peking Opera uses sheng, dan, jing, chou roles," write: "The clown (chou) lightens tense scenes with a wink, proving laughter needs no translation."

Personal Reflection: Why This Art Endures

Peking Opera isn’t frozen in time. Young artists blend tradition with innovation, like incorporating hip-hop rhythms into battle scenes. Its survival hinges on this adaptability—and on storytellers who convey its magic across languages. When an English essay captures the thunder of a luo gong or the whisper of a silk fan, it doesn’t just describe art; it becomes part of its legacy.

The next time you watch a performer’s sleeve swirl like ink in water, remember: you’re witnessing a language older than words. And that’s worth writing about.