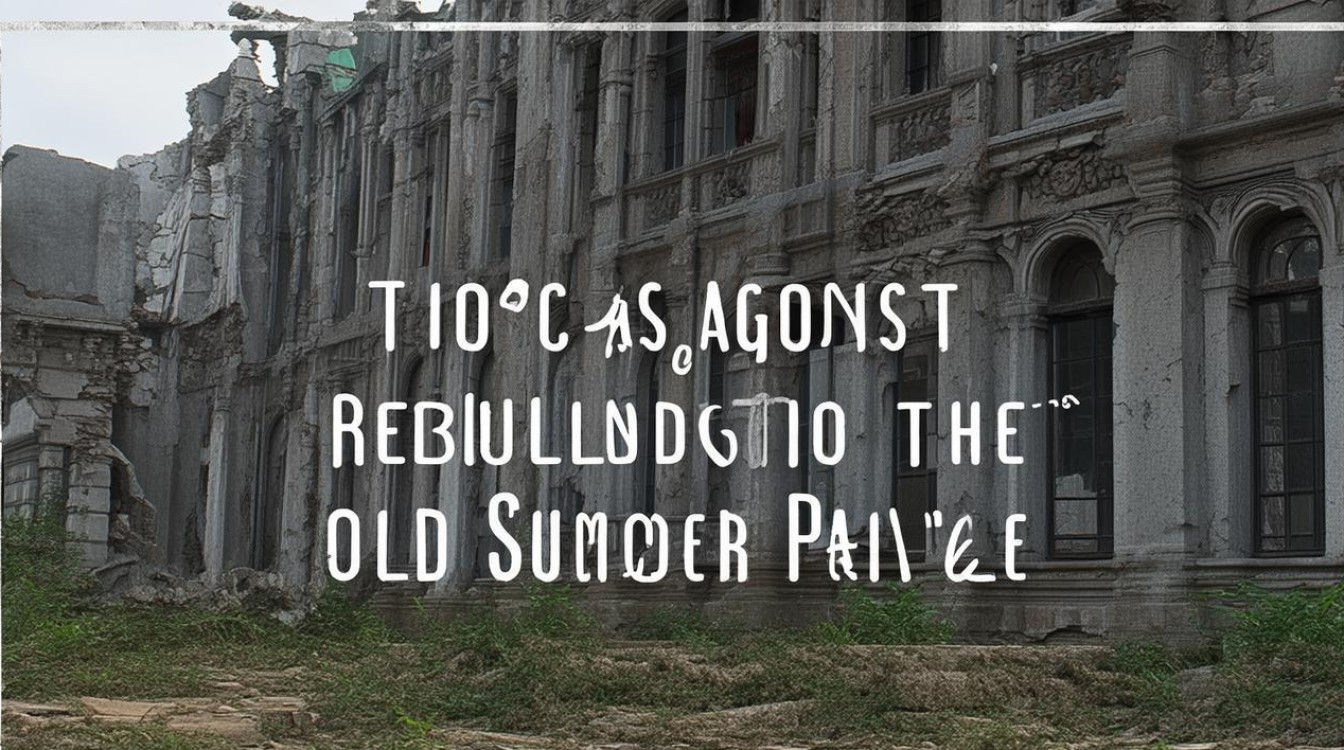

The Old Summer Palace, or Yuanmingyuan, stands as a hauntingly beautiful ruin in Beijing. Once a masterpiece of Chinese imperial architecture, it was looted and burned by Anglo-French forces in 1860. In recent years, debates about whether to rebuild it have intensified. While some argue restoration would heal historical wounds, others insist its ruins hold greater value. This article explores why rebuilding Yuanmingyuan would be a mistake.

Historical Authenticity Matters

Ruins are not just broken structures; they are raw testimonies of history. The Old Summer Palace’s current state—crumbling arches, overgrown gardens, and scattered relics—tells a story no reconstruction could replicate. Its destruction was a pivotal moment in China’s modern history, symbolizing the consequences of foreign aggression and internal weakness.

Rebuilding it would sanitize this painful past. Instead of confronting the reality of colonial violence, a restored Yuanmingyuan might inadvertently soften its historical impact. Authentic ruins force us to grapple with loss and resilience. A replica would risk turning history into a theme park.

The Cost of Reconstruction

Restoring Yuanmingyuan to its former glory would require astronomical resources. Historical records suggest the original palace took over 150 years to build, employing thousands of artisans and vast sums of imperial wealth. Today, replicating its intricate designs—especially the famed Western-style palaces—would demand cutting-edge technology and skilled labor.

Critics argue the funds could be better spent. China has countless cultural relics in urgent need of preservation, from ancient temples to endangered folk traditions. Pouring money into a symbolic reconstruction might divert attention from more pressing heritage projects.

The Challenge of Accuracy

Even with modern technology, rebuilding Yuanmingyuan accurately would be nearly impossible. Many original blueprints were lost during the palace’s destruction. While some European missionaries and artists documented its appearance, their accounts are incomplete.

Without precise records, any reconstruction would rely heavily on speculation. The result might be a pastiche of historical styles rather than a faithful revival. Worse, inaccuracies could mislead future generations about what the palace truly looked like.

The Value of Ruins in Modern Culture

Ruins have a unique power to inspire reflection. The Parthenon in Greece, the Colosseum in Rome, and the Angkor Wat complex in Cambodia all draw millions of visitors precisely because they are incomplete. Their decay invites contemplation about time, impermanence, and human ambition.

Yuanmingyuan’s ruins serve a similar purpose. Writers, artists, and filmmakers have long used them as symbols of resilience and memory. A rebuilt palace might lose this cultural resonance, becoming just another tourist attraction rather than a site of deep historical meaning.

Alternative Ways to Honor the Past

Instead of physical reconstruction, there are better ways to honor Yuanmingyuan’s legacy. Digital recreations, for example, could allow people to explore a virtual version of the palace without altering the ruins. Museums and educational programs could also deepen public understanding of its history.

Some scholars suggest leaving the ruins untouched but improving visitor facilities. Clearer signage, guided tours, and augmented reality tools could help people appreciate the site’s significance without erasing its scars.

The Risk of Commercialization

Historical sites often face pressure to become profitable. If Yuanmingyuan were rebuilt, there’s a real danger it could be turned into a commercial venture—filled with souvenir shops, staged performances, and ticket booths. Such changes might undermine its solemn historical role.

The current ruins, by contrast, resist commercialization. Their rawness discourages frivolous entertainment, ensuring the focus remains on history rather than profit.

A Symbol of Peaceful Remembrance

China today is vastly different from the Qing Dynasty. Rather than recreating an imperial relic, the nation has built new symbols of strength—modern architecture, technological achievements, and global influence. Yuanmingyuan’s ruins, left as they are, serve as a reminder of past vulnerabilities while highlighting how far the country has come.

Rebuilding the palace might send mixed messages. Would it celebrate imperial grandeur or mourn colonial destruction? The ambiguity could dilute its historical significance.

Final Thoughts

The Old Summer Palace is more than just a collection of broken walls. It is a monument to history’s complexities, a place where beauty and tragedy intertwine. Rebuilding it would not undo the past; it would only obscure it. By preserving the ruins, we honor the full weight of their story—one that deserves to be remembered, not rewritten.

Some wounds should not be erased. Some memories must remain visible. Yuanmingyuan, in its ruined state, does both.